I’ve been thinking about the Spanish-American War (April 21, 1898 – December 10, 1898) a lot lately and not only because I’m deep into my pal Lauren Willig’s wonderful historical novel, TWO WARS AND A WEDDING, set in Cuba at the height of the conflict.

The war, which ended the lives of more than 2,000 American soldiers, is the catalyzing event for IRISH EYES releasing December 2023. In the novel, Adam Blakely and his friend, Danny O’Neill sign on for what they believe to be a noble cause and a grand adventure, as did many real-life young men at the time. Once the pair leave the training camp in Tampa, Florida for the Cuban front, reality hits. Hard. Fighting the Battle of San Juan Heights, their Krag rifles are no match for the Spaniards’ smokeless Mausers. Both young men are wounded. Only Adam comes home to New York. Months later, humbled and hobbled, he shows up at the O’Neill family pub on Inishmore, an island on Ireland’s western coast, to fulfill his promise to Danny to deliver his rosary box to his sister, Rose. (Turns out Danny was a bit of a matchmaker, albeit from the grave).

Despite its brevity, the Spanish-American War seems to be having a moment these days but what was the war really about?

“Lie down—Lie down—Lie down”

Don’t Swear, boys, Shoot”

“Drive those Spaniards out.”

—Arthur C. Anderson, "K" company, 71st regiment, New York volunteers; a record of its experience and service during the Spanish-American war, and a memorial to its dead. Chas. H. Scott, 1900.

Relations between America and Spain had been strained for some time. Mind you, America at the turn-of-the-century wasn’t yet a superpower but more of an isolationist adolescent testing her wings. Many Americans were chafed by Spain’s presence so close to our shores, in Cuba and the Philippines, both Spanish possessions.

Cuban nationalists had been fighting to oust the Spanish as early as 1868. The third in a series of such uprisings, the Cuban War of Independence (1895 - 1898) caused serious upheaval to the region, including disrupting U.S. shipping interests.

The final straw was the sinking of the USS Maine, sent to Cuba by then President McKinley, ostensibly to safeguard Americans and American interests in the region. The battleship exploded in Havana Harbor on February 15, 1898, taking 266 American sailors with it. Whether the cause was a Spanish bomb, a Cuban mine or a boiler blast in the hull of the vessel was never determined, but the popular (and profitable) presumption was that Spain had sunk the ship.

As detailed in Ken Burns’ terrific three-part documentary, Citizen Hearst, media magnate William Randolph Hearst, the model for Orson Welles’s Citizen Kane, was very much the architect of the war. Why? Because wars sell newspapers.1 Using his newspaper empire as a big ole bullhorn, Hearst took every opportunity to call out Spain as the murderer of American sailors on the Maine, exaggerate Spanish attrocities against the Cuban people, and bully then President McKinley into declaring war. (Hearst as good as called for McKinley’s assassination in print).2

Once the war was on, Hearst promptly raised the cost of a hundred-paper newspaper bundle from fifty to sixty cents, as did his chief competitor, Joseph Pulitzer. After the war, when sales normalized, most publishers returned to the prewar price with the exception of Hearst and Pulitzer. Their intractability set off the Newsboys Strike of 1899, popularized in the 1992 Disney musical, Newsies.3

"Headlines don't sell papes. Newsies sell papes." — “Jack Kelly” (Christian Bale) in Newsies, 1992.

But it wasn’t only vitriolic news articles accompanied by grainy photos that brought the war home. The Spanish-American war was, if not the first, then certainly among the first military conflicts to have actual film footage. (Thanks, Thomas Edison)! Moving pictures were the shiny new tech of 1898.4 Footage of troops, ships, parades, and public personnages including Theodore Roosevelt with his Rough Riders brought the war to thrilling life for those back home.5

Roosevelt’s Rough Riders at drill in Tampa, Florida before departure to Cuba. American Mutoscope & Biograph picture catalogue. Library of Congress, Washington, DC.

Speaking of thrilling, while researching IRISH EYES, I discovered that I have an ancestor who fought in the war.

Friedrich Preuer, my maternal grandmother’s uncle, was born in 1878 in Germany, one of five children of Nicholas, a miner, and Catherine (nee Kossel). On March 25, 1891, the Red Star line ship, The Switzerland, landed in Philadelphia with Friedrich and his brother Ernest. Their parents and sister, Lena, followed two years later in 1893.

The family first settled in Pennsylvania where Nicholas found work as a miner. When he retired, they moved to Baltimore, Maryland and settled in Highlandtown, then a thriving blue-collar community of Germans and German Americans.

Like most immigrants of the era, Friedrich anglicized his first name, or had it anglicized for him, on arrival. Also like most immigrants then and now, he had to deal with people habitually misspelling his family name. (The many versions have certainly made work for this descendant).

When the U.S. declared war on Spain (April 25, 1898), Friedrich — now Frederick — not yet a naturalized U.S. citizen, volunteered for the fighting. (There was no draft in the Spanish-American War; the mass migrations of the 1880s and 1890s bolstered enlistment such that manpower wasn’t a problem). A private in the Sixteenth United States Infantry, Frederick was wounded in the battle of El Caney on July 1, 1898.

According to the September 22, 1898 Baltimore Sun, he successfully sued Harmony Lodge No. 4, Sons of Liberty (the Freemasons) and received $56 in sick benefits. Why he sued a fraternal organization I’m not sure. Was he employed by the Lodge rather than being a member and, if so, did his war wound cause him to miss work? If any of you have thoughts, intel, hypotheses etc., please share here in the Comments.

Back in Baltimore, Frederick married (in 1903), had a son, Elmer, who lived less than one year (1905-1906) and took a job at the National Brewery in Canton6. Now a coveted address for Charm City hipsters, Canton was then a working waterfront of factories, warehouses and cheap housing for the mostly migrant Irish, German and Polish workers employed there. It was there, outside the brewery building, eight years after surviving the Cuban front, that Frederick met his tragic end.

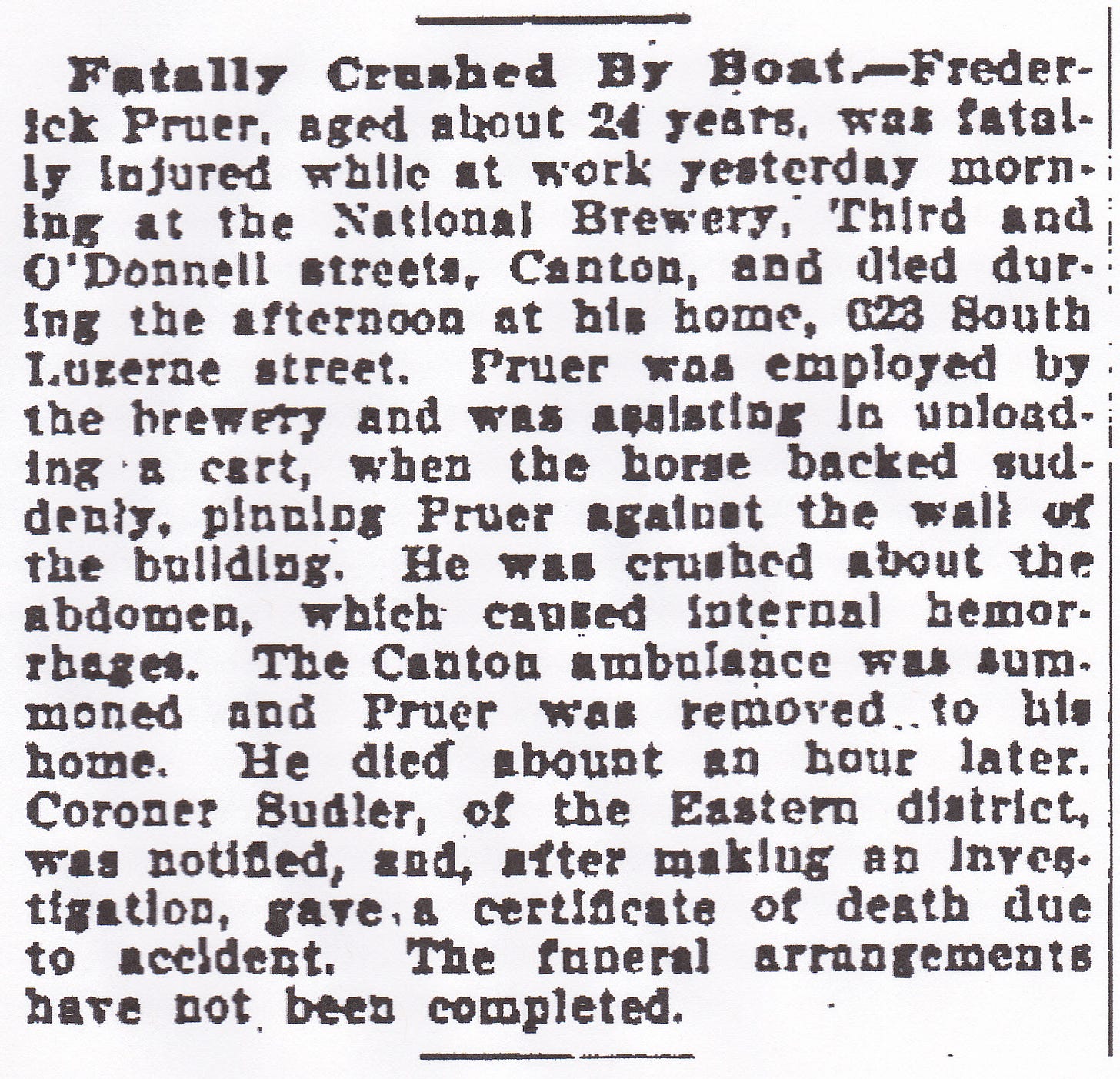

According to Frederick’s obituary in the May 30, 1906 Baltimore Sun newspaper, he was fatally crushed when a delivery cart horse bucked, pressing him between the cart and the warehouse.

Apparently Frederick’s widow didn’t merit naming. She was Martha Dever. They were married in 1903 when she was 20 and Frederick 25.7

This additional account, also in The Baltimore Sun, adds a few more details but gets Frederick’s age wrong.

Neither article remarks on the ambulance taking Frederick to his home rather than to an actual hospital. (Mercy Hospital, then a downtown charity hospital run by the Sisters of Mercy, was close by). As an immigrant working a manual labor job in a port city swelling with German and Polish newcomers, Frederick must have seemed a disposable commodity.

Next time here on History With Hope, I’ll post the Spanish-American war prologue from IRISH EYES that didn’t make it into the final book. Until then…

Prost, Uncle Fred!

Share this free public post with other history lovers.

Not yet a subscriber to History With Hope? You can fix that here!

IRISH EYES (releasing December 2023) spans twenty-five years of Gilded Age through the Jazz Age Manhattan, as seen through the eyes of spirited Irish-born Rose O’Neill. Read more here.

If this sounds farfetched, mind that at the height of his power (1930s), Hearst controlled the largest media empire in the country: 28 newspapers, a movie studio, a syndicated wire service, radio stations, and 13 magazines. He used his communications stronghold to achieve political power unprecedented in the industry, then ran for office himself. https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/films/citizen-hearst/

“After the shooting death of President William McKinley in September 1901, the New York Journal and a rival newspaper, the New York Sun, promptly engaged in a letters to the editor war over who inspired the assassin. The seeds of that war were planted April 10, 1901, when William Randolph Hearst's Journal attacked McKinley in an editorial that ended with the following words: "Institutions, like men, will last until they die; and if bad institutions and bad men can be got rid of only by killing, then the killing must be done."3 In June Hearst published another editorial that suggested "assassination can be a good thing." Hearst gave an example: "The murder of Lincoln, uniting in sympathy and regret all good people in the North and South, hastened the era of American good feeling." When a newspaper was accused of killing a president: How five New York City papers. Thornton, Brian. Journalism History; Las Vegas Vol. 26, Iss. 3, (Autumn 2000): 108-116.

The standoff turned ugly. For days, the boys and their backers blocked the Brooklyn Bridge, cutting off newspaper delivery to northern cities. Pulitzer and Hearst retaliated by hiring strikebreakers and protection men to rough up the protesters. Peace was restored on August 2nd when Pulitzer and Hearst agreed to buy back any unsold stock.

https://www.loc.gov/collections/spanish-american-war-in-motion-pictures/about-this-collection/

https://www.loc.gov/item/98500909

If you go to Baltimore, MD — it’s my hometown — you won’t have to wait long before someone breaks open a “Natty Boh.”

The following year, August 1907, 24-year-old Martha would remarry — Walter C. Richardson. She died October 27, 1939. Sources: Oct 30 1939, THE EVENING SUN, Obituaries, p 28. and 7 Aug 1907, BALTIMORE SUN, “Licensed to Wed,” p. 7; both extracted via newspapers.com

https://www.irs.gov/charities-non-profits/fraternal-organizations-what-constitutes-a-lodge-system