The Strike that 'Sparked' Labor Reform in Britain

The Bryant & May Match Factory Strike of 1888

Yesterday, I walked my first Writers Guild of America picket for the current strike, which started May 1st. I showed up for my four hour shift not quite sure what to expect. Admittedly, crowds and marching in public and going hours without a restroom aren’t super high on my wish list. Funny thing, though. What started out as a duty quickly turned into a moving meditation on gratitude.

Gratitude for the WGA strike captains who kept our energy, and voices, high.

Gratitude for the volunteers who kept us watered and caffeinated and fed, including pizzas contributed by the local chapter of the CWA (Communications Workers of America) — not on strike but there to show solidarity.

Gratitude for the members of SAG-AFTRA, also not on strike, at least not yet, and several other unions who walked with us.

Gratutude for actress Edie Falco (The Sopranos, Nurse Jackie) who turned out to walk with us and stayed for hours. As did this cutie.

Gratitude for the car and truck drivers who honked in support as they passed by our picket.

Gratitude for the police there to make sure everyone stayed civil and safe.

It wasn’t always so.

Years ago, I wrote a Victorian set romance, Vanquished. I remain fiercely proud of that book for a number of reasons, and not only for my “plus-size” suffragette leader heroine and working class hero, neither of which was exactly popular in publishing at the time. (To whit, the figure on the cover is pretty sylph-like).

Midway through the book, my heroine Callie — Caledonia — Rivers and hero, Hadrian St. Claire happen upon a strike in progress — at The Bryant and May Match Factory — a real event.

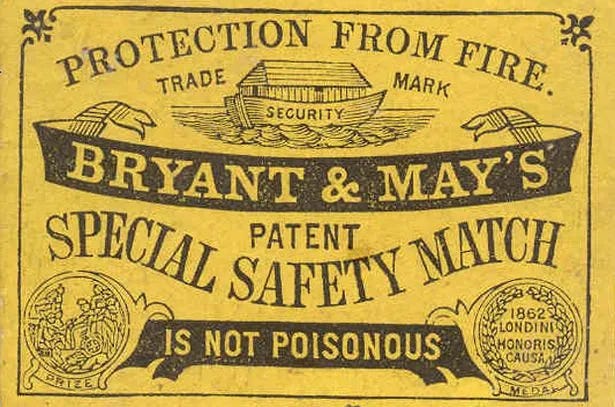

At one time the biggest factory in London, the Bryant and May Match Factory on Fairfield Road, Bow in East London1 was established in 1861 by two Quakers, William Bryant and Francis, to make safety matches.2

Safety match is a misnomer. The matches manufactured in the factory were not remotely safe for the women and girls tasked with making them. (Or for the young children who ingested them, but that’s a story for another post). The white phosphorous the match heads were dipped in was highly toxic. Prolonged contact brought on all manner of maladies, including burns to the skin, hair loss, shortness of breath, jaundice and eventually cancer of the jawbone known colloquially as Phossy Jaw.3

Charles Dickens wrote an expose on the horrors of Phossy Jaw (phosphorus necrosis) in 1852 for his weekly periodical, Household Words.4 (I briefly considered posting a photo of a Phossy Jaw sufferer here, then I remembered this Substack is called History with Hope and decided not to). Suffice it to say, Phossy Jaw was bad news. It was deforming and debilitating and, much like the Black Lung disease associated with coal mining, inevitable if you worked in a match factory over time.

So, in addition to working dawn to dusk for pittance pay, B&M employees could look forward to the irreversible destruction of their health and the halving of their lives. Even in Victorian England, it was a lot to sign up for.

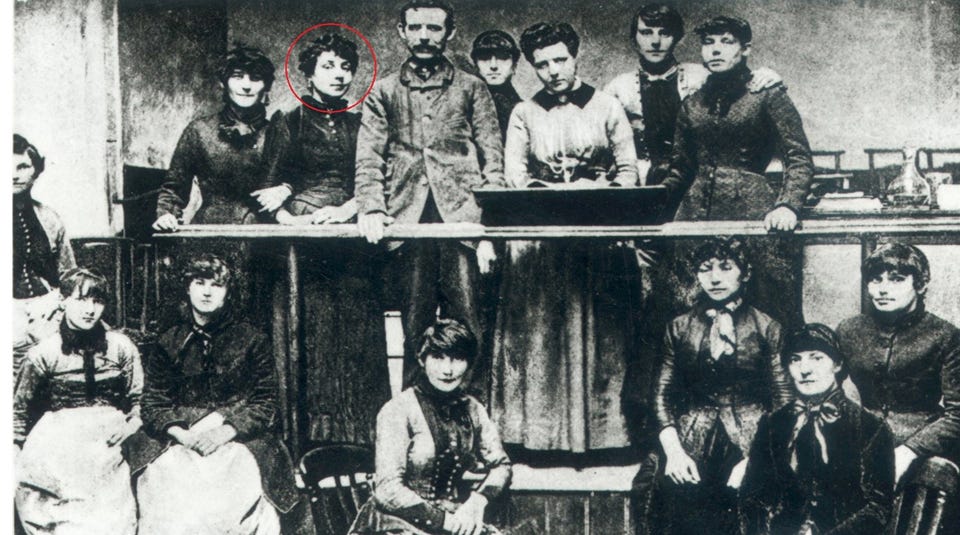

The Bryant and May Strike started June 23 1888 and initially involved 672 women and girls rather than the ragtag group of strikers I depict in Vanquished. Demands were heartwenchingly modest. Elimination of the system of fines—three pence to one shilling for talking, dropping matches, or going to the loo without the permission of the shift manager; a half-day’s pay for lateness.5

At the time, a week’s wages was less than five shillings. 6

An editorial entitled “White Slavery in London”7 by reformer Annie Besant (1847-1933) in her weekly newspaper, The Link detailed the B&M Factory’s abysmal working conditions: fourteen-hour days,8 poor wages, system of fines, abuse by foremen, and generally boring, tedious, and dangerous nature of the work.9

The company threatened to sue the paper for libel and attempted to strong arm the strikers into signing a statement denying the claims, but the women held firm. Predictably, their leader, Sarah Chapman was sacked.10

1,400 girls and women walked out on strike on July 5, 1888. The strikers sent the following unsigned letter to Besant.

My Dear Lady, – we thank you very much for the kind interest you have taken in us poor girls, and hope that you will succeed in your undertakings. Dear lady, you need not trouble yourself about the letter I read in the Link that Mr. Bryant sent you, because you have spoken the truth, and we are very pleased to read it. Dear lady, they are trying to get the poor girls to say that it is all lies that has been printed, and trying to make them sign papers to say it is lies; dear lady, no one knows what we have to put up with, and we will not sign them. We all thank you very much for the kindness you have shown to us. My dear lady, we hope you will not get into any trouble in our behalf, as what you have spoken is quite true; dear lady, we hope that if there will be any meeting we hope you will let us know it in the book. I have no more to say at present, from yours truly, with kind friends wishes for you, dear lady, for the kind love you have shown us poor girls. Dear lady do not mention the date this letter was written or I might have put my or our names, but we are frightened, do keep that as a secret, we know you will do that dear lady. 11

Besant’s subsequent articles and relentless campaigning brought the issue to the attention of MP’s in Parliament.12 There would be no turning back.

On July 18, Bryant & May conceded to all the women’s demands. On July 27, the workers established the Union of Women Matchmakers, the first British trade union for women.13 It was, albeit imperfect, the dawn of a new day.

In 1891, the Salvation Army opened its own match factory also in the Bow district of London, using only safe red phosphorus and doubling wages. A decade later, the factory was bought out by… Bryant and May.14 Fortunately, the 1888 strike remained evergreen in everyone's memory. In 1901, Bryant and May began using only safe red phosphorous imported from Sweden. In 1908, the White Phosphorus Matches Prohibition Bill passed in the UK; the law went into effect in 1910.15

B&M finally closed in 1979 and the work was moved to Liverpool. In 1988, the derelict site became one of east London's first urban renewal projects. Today, the former factory building is a gated community known as the Bow Quarter. An English Heritage blue plaque outside the entrance commemorates the strike.16

A fund for a memorial statue to honor the match girls and women remains underway.17

Share this free public post with other history lovers.

Not yet a subscriber to History With Hope? You can fix that here!

IRISH EYES (coming December 2023), Book 1 of my American Songbook series, spans twenty-five years of Gilded Age through the Jazz Age Manhattan, as seen through the eyes of spirited Irish-born Rose O’Neill. Read more here.

https://www.matchgirls1888.org/the-story-of-the-strike

In 1911, the Bryant and May Match Factory employed more than 2,000 women and girls. https://historicengland.org.uk/services-skills/education/educational-images/bryant-and-may-match-factory-bow-10984

Numerous sources including STRIKING A LIGHT by Louise Raw. https://www.amazon.com/Striking-Light-Bryant-Matchwomen-History/dp/1441114262

https://phossyjaw.wordpress.com/2012/03/05/phosphorus-necrosis-is-a-dreadful-disease/

https://archiveshub.jisc.ac.uk/search/archives/5501b19f-58f1-3699-b1f8-d183a6d4d658

Ibid

Per the National Archives UK: “In 1833 Britain abolished slavery in most parts of the Empire. To find out that women worked in such dreadful conditions in the match factories shocked many respectable Victorians.” https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/education/resources/what-was-the-significance-of-the-match-girls-strike-in-1888/

The women worked from 6.30am in summer and 8.00am in winter to 6.00pm. https://archiveshub.jisc.ac.uk/search/archives/5501b19f-58f1-3699-b1f8-d183a6d4d658

https://www.bl.uk/collection-items/newspaper-article-reporting-the-match-girls-strike

Ibid. Sarah Chapman was born in 1862 in Mile End, east London and at least by the time she was 19, was a matchmaking machinist. According to her great granddaughter, Sam Johnson, Chapman was one of the delegation of three who met with Annie Besant after the match girls marched to her office on Bouverie Street, and she was on the strike committee. Given the latter, she was almost certainly in the delegation that met MPs and would have discussed terms with Bryant & May at the end of the strike.

https://phm.org.uk/blogposts/the-match-girls-strike/

http://www.londonshoes.blog/2018/08/02/the-bryant-may-match-factory-in-bow-the-match-girl-strike-of-1888/

Ibid

https://www.matchgirls1888.org/phossy-jaw

Ibid

https://historicengland.org.uk/services-skills/education/educational-images/bryant-and-may-match-factory-bow-10984

https://www.matchgirls1888.org/matchgirls-statue

Another wonderful post.

These deep dives into history are amazing. Thank you!