"Racism is a grown-up disease, and we must stop using our children to spread it." — Ruby Bridges, Civil Rights Activist (1954 —)

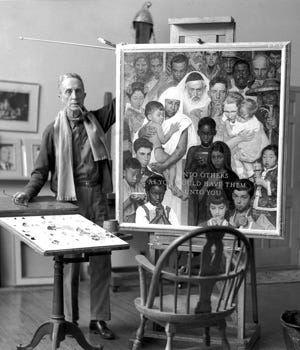

Years ago, I visited a Norman Rockwell exhibit showing at the now tragically defunct Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington, DC. What little I knew of Rockwell (1874-1978) came through his Saturday Evening Post covers — a whopping 322 canvases over 47 years. I also knew he was the favorite artist of President Ronald Reagan. Young, in graduate school and something of a culture snob, I was quick to dismiss Rockwell’s prolific output as the artistic equivalent of meatloaf — some are better than others but overall, the same basic recipe. An idealized, salt-of-the-earth depiction of an America that, even then, many people seemed eager to turn back to. But the exhibit was on temporary loan, I had a family friend in town who was a huge Rockwell fan, and the Corcoran, with its uber air-conditioned, classically arranged interiors was a perfect refuge from a sweltering DC summer day. Why not, I thought?

Entering, I was blown away by the magnitude and power of Rockwell’s colossal canvases, one painting per week from 1916 to 1963. Until then, I’d only experienced Rockwell’s portfolio as photographs reprinted in books and magazines. Seeing them mounted on gallery walls side-by-side with the photographs that inspired them — Rockwell painted from “reference photographs,” mostly shoots he himself directed1 — I was struck by not only their size and scale, but also by the artist’s careful composition, lively brush strokes, and deeply nuanced insight into what makes we Homo sapiens tick.

In 2018, I visited another Rockwell exhibit, “Rockwell, Roosevelt & the Four Freedoms,” this time at the New York Historical Society.2 Learning that, during his Saturday Evening Post tenure, Rockwell was prohibited from depicting African Americans in roles other than domestics shocked me. In retrospect, it shouldn’t have.3

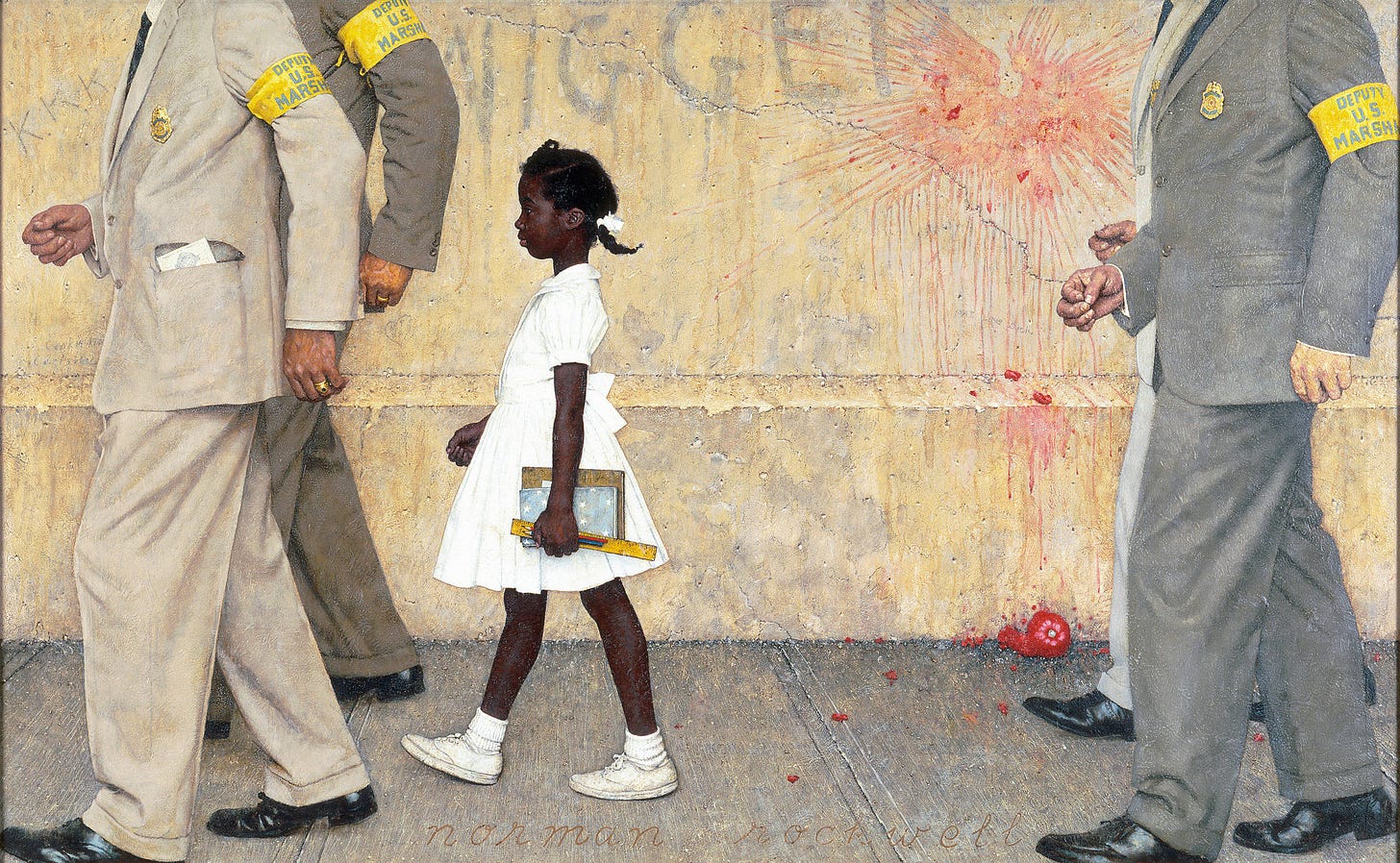

Today, May 17th, marks the sixty-ninth anniversary of Brown vs. Board of Education, a cornerstone case in the Civil Rights Movement and the inspiration for one of Rockwell’s best known paintings, “The Problem We All Live With.”

Brown v. Board of Education challenged the “separate but equal” doctrine that had kept Black citizens segregated since the Civil War, including separate schools for Blacks and whites. The plaintiff in the case was Oliver Brown who in 1951 filed a class-action suit against the Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas for denying his daughter, Linda, admission to Topeka’s all-white elementary schools.4

By the time the case came to the Supreme Court, Brown v. Board of Education comprised five cases: Brown itself, Briggs v. Elliott (filed in South Carolina), Davis v. County School Board of Prince Edward County (filed in Virginia), Gebhart v. Belton (filed in Delaware), and Bolling v. Sharpe (filed in Washington, D.C.).5 Future justice Thurgood Marshall, then head of the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund,6 served as chief attorney for the plaintiffs.7

On May 17, 1954, the Court unanimously ruled that school segregation violated the 14th Amendment, which guarantees all citizens—of all races—“equal protection under the law.”8

Pushback from white politicians and parents, especially in the “Jim Crow” South, was fierce,9 nowhere more so than in Louisiana. Ordered to commence school desegregation, the Bayou State deliberately dragged its feet. Pressure from Federal Judge Skelly Wright finally forced the school board to begin desegregation on November 14, 1960.10

Rockwell didn’t paint “The Problem We All Live With” until 1963, after he had parted ways with The Post. The canvas, his first assignment for Look magazine,11 showed six-year-old Ruby Bridges being escorted by four U.S. marshals to her first day at an all-white school in New Orleans. The school, William Franz Elementary, was just a few blocks from Bridges’ home.

Bridges was born September 8, 1954, the same year as the Supreme Court ruling. By the time she started kindergarten, many schools still hadn’t complied with the Court’s ruling. A call from local NAACP leaders encouraged her parents to challenge school segregation in New Orleans. Their courage in saying yes exacted an incredible cost. Ruby’s father was fired from his job and her grandparents, sharecroppers in Mississippi, were forced off their land. White parents pulled their children from school so they would not have to sit with Ruby, who spent a year in a classroom by herself.12

Barbara Henry, a young white teacher recently relocated from Boston, was the only faculty member who would teach Bridges. Neither missed a single day of school that first year.13

Rockwell followed “The Problem We All Live With” with “Murder in Mississipi” (1965), which depicts the 1964 execution murders of four civil rights activists in Philadelphia, Mississippi during Freedom Summer, a voter registration drive aimed at increasing the number of registered Black voters in the state.14

Bridges went on to graduate from a desegregated high school, become a travel agent, marry and have four sons. She wrote two books about her historymaking experience and in the nineties gave lectures with her former teacher, Barbara Henry. In 1999, she established The Ruby Bridges Foundation to promote tolerance and create change through education. Though she and Rockwell never met, she served on the board of the Norman Rockwell Museum in Vermont.15

President Barack Obama borrowed “The Problem We All Live With” for a special White House exhibition to commemorate the fiftieth anniversary of Bridges’ brave walk. Bridges was invited to the Obama White House to view the painting mounted on the wall outside of the Oval Office.16

Share this free public post with other history lovers!

Not yet subscribed to History With Hope? You can fix that here!

IRISH EYES (coming December 2023), Book 1 of my American Songbook series, spans twenty-five years of Gilded Age through the Jazz Age Manhattan, as seen through the eyes of spirited Irish-born Rose O’Neill. Read more here.

https://www.cbsnews.com/pictures/the-making-of-norman-rockwells-saturday-evening-post-covers/12/

https://www.nyhistory.org/exhibitions/rockwell-roosevelt-four-freedoms

In an interview later in his life, Rockwell recalled that he once had to paint out an African American person in a group picture since The Saturday Evening Post policy dictated showing African Americans in service industry jobs only. http://www.nrm.org/thinglink/text/ProblemLiveWith.html

https://www.history.com/topics/black-history/brown-v-board-of-education-of-topeka

https://www.archives.gov/education/lessons/brown-v-board/timeline.html

In 1967, President Lyndon B. Johnson appointed Marshal to the Supreme Court, making him the first African American justice.

https://www.history.com/topics/black-history/brown-v-board-of-education-of-topeka

Ibid. In 1896, the Supreme Court ruled in Plessy v. Ferguson that racially segregated public facilities were legal, so long as the facilities for Black people and whites were equal. The ruling constitutionally sanctioned laws barring African Americans from sharing the same buses, schools and other public facilities as whites.

Jim Crow laws were a collection of state and local statutes that legalized racial segregation. https://www.history.com/topics/early-20th-century-us/jim-crow-laws

http://www.nrm.org/thinglink/text/ProblemLiveWith.html

Published in Des Moines, Iowa, Look (1937 to 1971) was a biweekly general-interest magazine that leaned heavily on photos and photojournalism and published primarily lifestyle and human interest articles.

https://www.kennedy-center.org/education/resources-for-educators/classroom-resources/media-and-interactives/media/visual-arts/norman-rockwell--the-problem-we-all-live-with/

https://jtojhumanrights.org.uk/ruby-bridges-barbara-henry/

https://www.nrm.org/MT/text/MurderMississippi.html

https://www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/ruby-bridges

https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/blog/2011/07/15/president-obama-meets-civil-rights-icon-ruby-bridges

I remember watching Ms Bridges walking to school surrounded by federal agents. I thought she was incredibly brave. I still do. She was one of my heroes. I remember asking my father why she just couldn't go to her neighborhood school like I did. I didn't agree with the answer he gave me: that people hated her because of her color. I didn't understand them then and still don't.

I was unaware, but not surprised, that *The Post* had prohibited Rockwell from portraying Black Americans in anything other than domestic laborers.

Brown v. BoE was such a significant Supreme Court ruling, I remember having to memorize the year of it.