Remembering The Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire

The Workplace Disaster That Changed the Landscape of U.S. Labor Reform

This Tuesday, March 25th marks the 114th anniversary of the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire, the deadliest workplace disaster in New York until 9/11. As the niece of a former garment worker, I write about the fire every year to do my part in ensuring we don’t forget the workers, almost all women and girls, who perished in what was in every way a preventable tragedy, as well as the important labor reforms that resulted from it — reforms led by women.

Housed in the Asch Building (today the Brown Building of New York University), the Triangle was one of the largest East Coast manufacturers of the shirtwaist, the high-necked blouse that was a wardrobe staple for turn-of-the-century women. Despite being in a modern (1901) skyscraper (10 floors) touted as fireproof, the factory owners’ unsafe workplace practices and conditions e.g., blocking stairwells with sewing machines and other equipment, locking workroom doors from the outside, refusing to allow fire drills, and failing to fix broken elevators combined to create a catastrophe.

At 4:45 pm on Saturday, March 25, 1911, just 15 minutes before quitting time,1 flames broke out on the Triangle’s eighth floor. The fire swept through the ventilator shafts to engulf the ninth floor workroom and tenth floor offices. Within 30 minutes, 146 workers were dead and 78 injured, most immigrant women and girls, the youngest just fourteen years old.

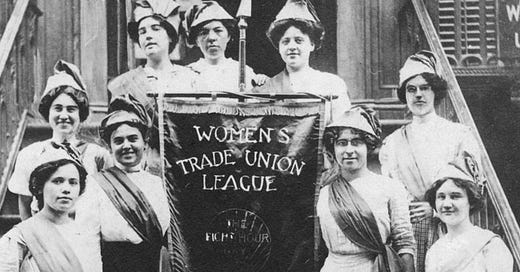

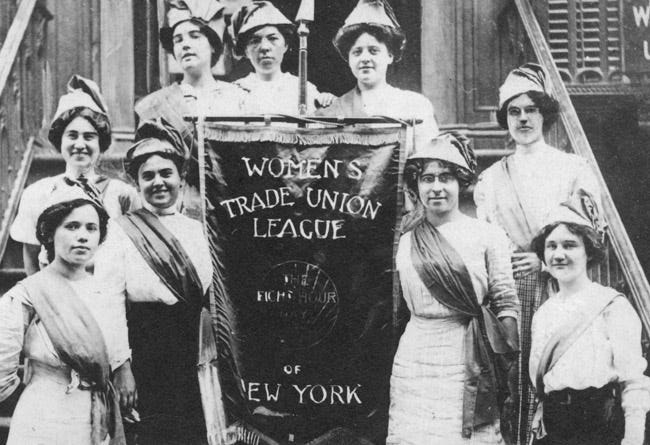

Afterward, public protests led by the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union brought about many of the “standard” workplace safety measures we take for granted today, such as sprinkler systems, fire drills, and an eight-hour workday.

Workers’ rights advocate Frances Perkins2 was among the New Yorkers to witness the fire. On the recommendation of former U.S. president Theodore Roosevelt, a Republican, Perkins served as executive secretary of New York State’s Committee on Safety, which led to the establishment of the New York State Factory Investigating Commission. Later, as Secretary of Labor (1933 - 1945) under another Roosevelt president, Franklin Delano, a Democrat, Perkins famously stated, “The New Deal began on March 25th, 1911, the day that the Triangle factory burned.”

For more on the Triangle Fire, read the article I wrote for The Irish Times and listen to my podcast, “The Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire of 1911: An Emigrant’s Experience” written and produced with Fin Dwyer for The Irish History Podcast.

Save the Date(s)

For those of you in or around southern New Jersey and/or New York City, I hope you’ll join me at the following book signing events for STARDUST and IRISH EYES.

Saturday, March 29th

Barnes and Noble, Holmdel, NJ

The Commons at Holmdel

2130 Route 35, Holmdel, NJ | 732-203-6180

12 noon-3pm

Tuesday, April 22nd

Barnes and Noble Upper West Side Manhattan

2289 Broadway @ 82nd St., New York, NY 10024 | 212-362-8835

6pm.

Keep up with all my events here.

Find IRISH EYES and the sequel, STARDUST, on Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Bookshop, Target, Walmart and wherever books are sold.

Signed copies are available at these booksellers:

Barnes & Noble Upper West Side, Manhattan

Barnes & Noble, Brick Plaza, NJ

Barnes & Noble, Holmdel, NJ

Barnes & Noble, Pikesville, MD

Book Culture, Manhattan (2 locations)

The Corner Bookstore, Manhattan

Posman Books Chelsea Marketplace, Manhattan

Thunder Road Books, Spring Lake, NJ

The Comfort Zone, Ocean Grove, NJ

Enjoy this short excerpt from IRISH EYES narrated by my heroine, Rose.

146 Men and Girls Die in Waist Factory Fire;

Trapped High Up in Washington Place Building;

Street Strewn with Bodies; Piles of Dead Inside

—The New York Times, March 26, 1911

The fire at the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory hit me hard and not only because it brought back The Windsor. Our Nora worked as a sewing machine operator on the factory’s ninth floor, a good job for a girl of seventeen, or so Pat and Kathleen saw it.

Around a quarter to five, I heard the first of a succession of sirens. I finished giving my customer her change and stepped outside to better discern their direction. Seeing Mrs. Katz pacing outside the bakery, I made my way over.

“A four-alarmer at least,” I said, for my years as a fireman’s wife had trained my ear. “Any idea where it is?”

She turned to face me, flour on her cheek and fear in her eyes. “The Triangle. My Lilith works there.”

I braced a hand to the bricks, feeling as if I’d been gutted. “So does our niece.”

We took a taxi to Washington Place, the plume of smoke in the sky thickening with every passing block. Our driver pulled up to the adjacent Washington Square Park, and my chest tightened, for the scene playing out was The Windsor Hotel, only worse.

The Asch building, which housed the factory on its upper floors, was banded by flames and belching black smoke. The first fire trucks had arrived. It was painfully apparent that the hoses were too short to reach the ninth floor, where most workers, including our girls, slaved for pittance pay.

Helpless, we waited in the park, cordoned off and packed with people, many of whom, like ourselves, had loved ones within. Anytime I spotted a man in uniform, I rushed up and demanded news, but not even the policemen stationed onsite seemed to know much.

“Auntie Rose.”

Nora pushed through the barricades and rushed up, Lilith with her. Neither girl seemed to have suffered so much as a singed eyelash. At the sight of her child, Mrs. Katz dissolved into a puddle, the tears she’d bravely held back rushing down her cheeks.

I clasped Nora close, my own eyes swimming. “I thought for sure…”

“The foreman sent Lily and me out for sandwiches. When we got back—” She pulled back to show me the crushed brown bag and burst into tears.

Nora and Lilith were among the fortunate few. Most of the fire’s one hundred and forty-six casualties, nearly all immigrant women and girls from Eastern Europe and Southern Italy, would come from the ninth floor. Some victims succumbed to the flames; others jumped. Clasping hands for courage, girls leapt in pairs, tearing through the rescue nets too fragile to hold them. Meanwhile, the factory owners, the so-called Shirtwaist Kings, Max Blanck and Isaac Harris and their coterie, climbed out their tenth-floor office and escaped onto the rooftop of the adjacent law school.

The fire dominated the news for months. It came to light that the factory had experienced four prior fires and been reported as unsafe to the city’s Building Department due to an insufficiency of working exits – fire escapes blocked by equipment and bolts of fabric – as well as workroom doors locked from the outside to prevent unauthorized breaks. Owner avarice, including denying employee requests to practice fire drills, had greatly contributed to the calamity.

For once, political allegiances took a back seat to justice. Nativist or newcomer, Christian or Jew, Protestant or Catholic, Republican or Democrat – the aggrieved public gathered in churches, synagogues, and, lastly, the streets. The International Ladies’ Garment Workers Union lobbied for a citywide day of remembrance for the dead, no, murdered girls. Labor unions, religious communities, social reform organizations, and political groups, including Tammany, joined forces to demand real progress in worker protections. Within a month of the fire, the New York State Factory Investigation Committee was created to review conditions in factories and sweatshops across the state. Joe lost no time in wrangling himself a seat on it, not that I begrudged him the appointment. With his first-hand knowledge of firefighting, he was ideally suited to do some good.

Looking back, I can’t say I was happy, but having finally given up the tug-of-war with Tammany for my husband, I was more at peace than I’d been in years.

And then, one damp December evening, everything changed.

Copyright Hope C. Tarr

Then the work week was six days, with Saturday hours ending “early” at 5 pm. The only full day off was Sunday, the Christian Sabbath.

Perkins was the first woman to hold a U.S. presidential cabinet position.

We should never forget.

Important, also, as we're honoring women with Women's History Month.