Growing up, I used to love watching my mom get ready to go out. Taking pride of place on her dresser top was a bottle of Chanel No. 5. Chanel No 5 was special occasion perfume reserved for going someplace “fancy.” To my best recollection, I don’t think she ever finished the bottle.

Nor would she, or any other Chanel customer, have known of or believed the dark history beneath the signature scent’s chic mystique. A history rooted in the Second World War, in Nazi occupied Paris, where antisemitism and opportunism converged and were taken to extreme, borderline evil lengths by the perfume’s founder, iconic fashion designer, Gabrielle “Coco” Chanel (1883 - 1971).

Abandoned by their widowed father, Chanel and her sisters grew up in a convent orphanage where they learned to sew. While aspiring to be a cabaret performer, young Chanel found steady work as a seamstress. She also found a string of well-heeled lovers who brought her into contact with an international aristocracy, including Winston Churchill, Britain’s future Prime Minister. Years later, Chanel’s friendship with Churchill would be her saving.

Chanel’s breakout moment as a designer was the jersey dress,” a loosely constructed frock made of “jersey,” a type of woolen knitwear. As is often the case, necessity was the mother of invention. At the advent of the First World War, silk was earmarked for parachutes, not party dresses. As more and more women entered the workforce to take over for men fighting on the Front, demand for these chic, simple dresses that moved with the body rather than constrained it exploded.

In 1918, Chanel set up shop in Paris at 31 Rue Cambon and expanded her offerings to include jewelry and perfume. In 1922, she collaborated with Ernest Beaux, a French-Russian perfumer, to create a scent that would make its wearer “smell like a woman, and not like a rose.” Beaux presented Chanel with a numbered series of perfume samples to choose from. She picked the fifth, hence No. 5.1

Demand for No. 5 quickly outstripped the limited supply made by Beaux in his small laboratory. Théophile Bader, founder of the department store Galeries Lafayette, wished to sell No. 5, so he introduced Chanel to his friend Pierre Wertheimer.2

In 1924, the trio incorporated as Les Parfums Chanel. According to their deal, Wertheimer would manufacture No. 5 in his factory and receive 70 percent of the profits. Bader earned 20 percent as a finder's fee. Chanel herself received just 10 percent. Feeling she had been cheated, Chanel filed lawsuit upon lawsuit to get a larger share of the profits.3

On Friday, June 14, 1940, German tanks rolled into Paris. Before the sun set, the Swastika flew from the Eiffel Tower. The City of Light would remain under the heel of the Third Reich for four brutal years.

The Jewish Wertheimers fled to New York. Chanel shuttered her by then five shops, fired her 4,000 workers, and prepared to leave as well. Ultimately, she tarried too long. When her chauffeur refused to drive her powder blue Rolls-Royce through the thronged city streets, she resigned herself to staying and installed herself at the Hôtel Ritz, by then the headquarters for the Nazi high command. There she embarked on an affair with Baron Hans Günther von Dincklage, a German aristocrat and spy for the Abwehr.4

The Nazis lost no time in seizing all Jewish-owned property and businesses. Chanel used her “Aryan” status to petition German officials for sole ownership of Les Parfums Chanel. But unbeknown to her, the Wertheimers, anticipating the forthcoming Nazi mandates against Jews had, in May 1940, signed over control of Parfums Chanel to Felix Amiot, a French businessman and industrialist as well as a collaborator who sold arms to the Nazis. At the war’s end, Amiot returned Parfums Chanel intact to the Wertheimers.5

Paris was liberated on August 19, 1944. Chanel was arrested by French Resistance forces on allegations of spying for the Nazis but released the next day. While we may never know for certain, historians speculate that friends in high places, perhaps Churchill himself, intervened on her behalf, sparing her the punishments meted out to other “horizontal collaborators.” If so, Churchill likely was motivated by more than a soft spot for the good old days of country house parties. Chanel’s connections to the British aristocracy ran to the royal family, notably the Duke and Duchess of Windsor, the former Edward VIII and his American wife, Wallis Simpson. The couple had been thick with Hitler as well as at the center of at least one plot to reinstate Edward as a puppet king of England. Exposing Chanel would have meant releasing a devastating scandal just as Britain was struggling to rebuild after a brutal six year war.6

Released, Chanel posted a note to her shop window offering free Chanel No. 5 to all American GIs. She then decamped to Switzerland to join von Dincklage. While living in exile, she continued her legal battle with the Wertheimers. Finally, the family renegotiated a deal: rather than 10 percent of all French sales of No. 5, Chanel would have 2 percent of world sales, and the right to produce her own scents sans “5.” She never did.

In 1954, at the age of 71, she returned to Paris and re-opened her couture house, presenting her first collection in fifteen years to mixed reviews.7 By then, few Parisians wished to dredge up the dark days of the Occupation, including Pierre Wertheimer. Seizing the opportunity to boost flagging sales of their fragrances, he negotiated his final deal with Chanel: the Wertheimers would pay for her rue Cambon headquarters, personal expenses and taxes for the rest of her life in return for control of her name for perfume and fashion. (She retained creative control). As Chanel had no heirs, upon her death the family would receive her perfume royalty payments, too.8 9

Chanel died on January 10, 1971, at the Ritz where she had lived for more than 30 years.10 It wasn’t until 2014 that French intelligence declassified and released documents confirming her role as a spy for Germany in World War II.11 Chanel’s spying activities are chronicled in Hal Vaughan’s fascinating biography, Sleeping with the Enemy. Coco Chanel’s Secret War, which I am reading now.

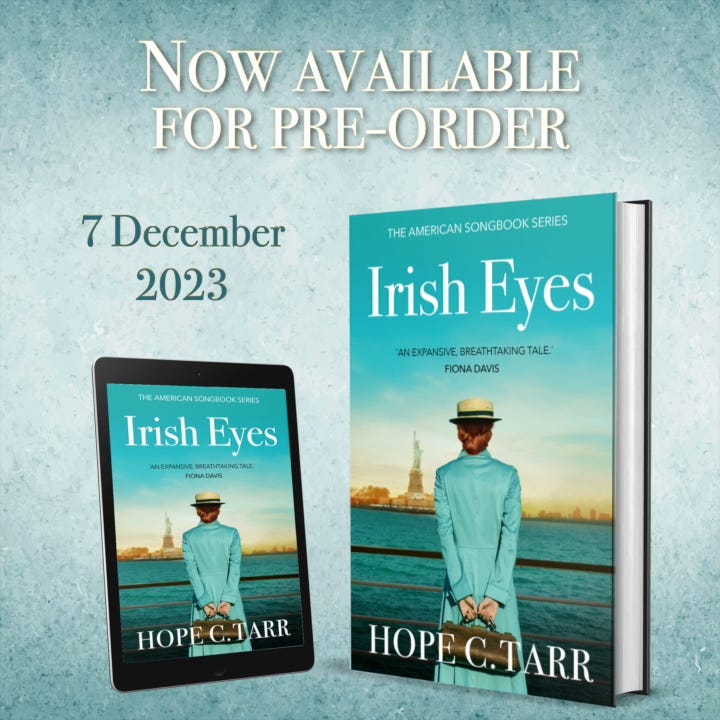

Further to the subject of books, this week I received Advanced Reading copies of Irish Eyes. As any author knows, there’s nothing like holding your physical book. Enjoy my unboxing video below!

Share this free public post with other history lovers.

Not yet subscribed to History With Hope? You can fix that here.

IRISH EYES, the launch of my American Songbook series, releases December 7. Preorder the novel on Amazon, Barnes & Noble and wherever books are sold.

https://www.cnn.com/style/article/coco-chanel-fashion-50-years/index.html

https://www.nytimes.com/2002/02/24/magazine/the-power-behind-the-cologne.html

Ibid.

Mazze, Tilar J. The Hotel on Place Vendome: Life, Death, and Betrayal at the Hotel Ritz in Paris. Harper: March 18, 2014.

https://www.nytimes.com/2002/02/24/magazine/the-power-behind-the-cologne.html

Vaughan, Hal. Sleeping with the Enemy. Coco Chanel’s Secret War. Knopf: 2011.

https://www.swissinfo.ch/eng/culture/how-coco-chanel-spent-her-exile-in-switzerland/46264712

https://classicchicagomagazine.com/tag/hans-gunther-von-dincklage/

https://www.nytimes.com/2002/02/24/magazine/the-power-behind-the-cologne.html

https://www.swissinfo.ch/eng/culture/how-coco-chanel-spent-her-exile-in-switzerland/46264712

She was known by the code name "Westminster" as a former lover of the Duke of Westminster.

Fascinating. I was aware of some of it, but not the full story.