Drawing Inspiration from History

“Truth is stranger than fiction, but it is because Fiction is obliged to stick to possibilities; Truth isn't.” — Mark Twain

In my upcoming historical novel, IRISH EYES (December 2023, Lume Books), my immigrant heroine, Rose, takes a job as a chambermaid at the posh Windsor Hotel in Manhattan. On March 17, 1899, St. Patrick’s Day, Rose is cleaning an upper guest room and sneaking peeks of the passing parade, including the handsome firemen in their dress blues, when the fire breaks out. Trapped, she contemplates jumping rather than being burned. Fortunately for Rose, fire captain Joe Kavanaugh has never backed away from a fire in his life and he’s not about to start. He mounts a daring a rescue. Rose survives but the fire changes the course of her life forever.

What follows is an accounting of the real Windsor Hotel fire, which remains New York’s deadliest hotel fire and its worst commercial disaster until the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire of 1911. (For more on that, have a listen to my podcast, “The Triangle Shirtwaist Fire of 1911: An Emigrant’s Experience”), a collaboration with Fin Dwyer’s Irish History Podcast.

“The Most Comfortable and Homelike Hotel in New York”

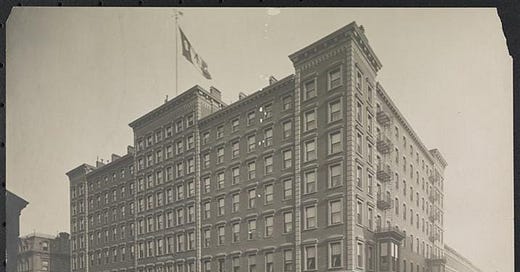

Advertising itself as “the most comfortable and homelike hotel in New York,” the Windsor Hotel opened in 1873, operated by Chicago hotelier Warren F. Leland. Its proximity to the new railway terminus at Grand Central, predecessor to the current station, and siting on Upper Fifth Avenue portended success in an era when hotel living was gaining popularity among the well-heeled.

Until then, Upper Fifth Avenue had been almost exclusively residential, a posh enclave for the Gilded Age’s wealthiest New Yorkers. The sumptuous brownstone flanked by mayoral lampposts at 579 Fifth Avenue was home to Helen Gould, daughter of the late railroad magnate, Jay Gould, then the ninth richest man in America. Further up Fifth between 51st and 52nd Streets, William K. Vanderbilt’s Petit Chateau at № 660 stood next door to the Triple Palace built by his father, William Henry. Taking up an entire city block between 46th and 47th streets, at first the Windsor wasn’t without its skeptics, but the handsome seven story brick-and-brownstone hotel soon earned its place in the neighborhood, drawing the fashionable set to its canopied entrance.

The Windsor was a small city unto itself. All the practical amenities were provided on premises — barber’s shop, grocery, general storerooms, telegraph office, several restaurants serving three meals a day, and 139 public and private bathrooms outfitted with hot and cold taps.

The hotel’s interior mirrored the luxury that most of its guests had come to expect. In the main hall, a curved marble grand staircase spiraled upward to a magnificent plaster-work ceiling capped by a soaring rotunda. Rosewood paneling inlaid with satinwood and black walnut festooned the main corridors and public rooms; the latter included a large drawing room and two adjoining parlors, all beautifully furnished and elegantly appointed. The grand octagonal salon was a popular spot for society weddings and other celebrations.

The five hundred guestrooms were kitted out in curtains, bed hangings, and carpets of crimson, blue, or purple velvet and equipped with private bathrooms, an almost unheard of luxury at the time. A two-bedroom suite with private parlor ran to $200 a week, the equivalent of more than $6,000 today.

It wasn’t only luxury for which guests at the Windsor paid top dollar. It was the assurance of safety. In each guestroom, hidden behind the heavy velvet drapes and lace curtain liner, a coil of rope was hooked to the sill, the length of which reached to ground-level. Theoretically, a fire-trapped guest could unwind the rope and descend to safety.

The hotel registry read as a Who’s Who of the day. Touring opera divas, captains of industry, financiers, politicians, and visiting heads of state were among those who treated the Windsor as their home away from home. Abner McKinley, brother to the then U.S. President, occupied a suite of rooms on the third floor with his wife and their disabled daughter. For years the celebrated soprano Adelina Patti kept a standing suite of rooms on the third floor overlooking 47th Street, outfitted with a private billiard table at her behest.

Not all hotel guests were of the champagne and caviar set. Among the hotel’s long-term residents was Mrs. Dora Gray Duncan, a divorcee from San Francisco who gave children’s dance classes in a fourth floor parlor to support herself and her four children, including then twenty-two-year-old Isadora. The episode, chronicled by Duncan in her memoir, My Life, would leave the future dance sensation with a lifelong dislike of hotels.

St. Patrick’s Day Fire

Friday, March 17, 1899 brought a longed for breath of spring, welcome anytime but especially so as it was St. Patrick’s Day. Drawn out by the warm weather, spectators had assembled along Fifth Avenue since early that morning, staking out their spots along the roped off sidewalk to view the parade as it made its way down Fifth Avenue. By midday, thousands stood three-deep, many with shamrocks pinned to their hats and lapels and waving miniature Irish flags, then a harp upon a field of green.

Ideally situated along the parade route, the Windsor was fully booked with both local and out-of-town guests. That afternoon, hotel guests stationed themselves along the banks of windows lining the concourses looking down onto Fifth, sipping champagne, several of the gentlemen smoking.

Shortly before 3:00 pm, drums and bagpipes and brass bands announced the parade’s approach. The highlight of the procession was the fire wagons wrapped in bright green and orange bunting, the strapping firemen decked out in navy blue dress coats done up with double breasted silver buttons. Carrying presentation trumpets filled with daffodils, many were anticipating the string of Bowery saloons where they’d finish out the day.

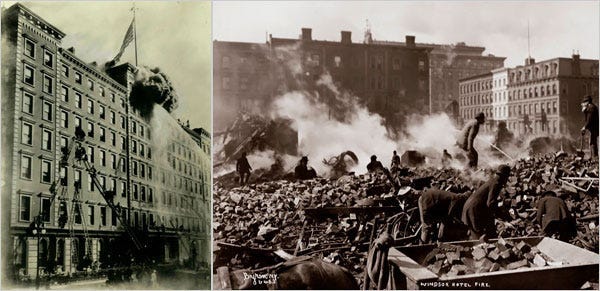

A familiar burning stench stopped the procession just as it came up to 47th Street. Across the avenue, fire blanketed the Windsor’s first four floors, black smoke blowing forth from the windows fronting Fifth as well as those on the 46th and 47th Street sides.

The marchers stalled to a scratchy stop. Spectators stood dumbstruck, no longer watching the parade but instead staring up at the hotel, its cornices and fire escapes crawling with people. More of the trapped stood at the open windows wailing to be saved.

Inside the hotel, pandemonium broke loose, guests and staff grabbing what pets and possessions they could carry and fleeing to the stairwells and other exits, only to be beaten back by impenetrable walls of smoke and flame. Those who could ran back to their rooms only to discover that the window ropes were useless now that the hotel’s bottom four floors were wrapped in flames. Several tried anyway, only to have the ropes break before they reached the sidewalk.

By 3:10 p.m., the fire had torn through the hotel, devouring the sumptuous carpets and curtains, wall hangings and artwork and sealing off the stairways and elevators. At least a dozen of the desperate flung themselves from the windows rather than be burned, the shriek of sirens joining the screams of onlookers helpless to do other than stand by and watch.

The fire went to five alarms but the pedestrians packing not only Fifth but the 46th and 47th side streets slowed the fire engines’ progress. By 4:30 p.m., the hotel was reduced to rubble; only the chimney stood. Several fire engine companies stayed onsite through the night, wetting down the still smoking ruins.

Fire victims flooded nearly all the city hospitals — Bellevue, New York, Flower, Harlem, Roosevelt, Presbyterian, and St. Vincent’s. Neighboring heiress Helen Gould opened her home as a makeshift hospital and served hot meals to the firemen. Several hotels provided shelter to the displaced, including the hotelier, Mr. Leland, who lost both his wife and twenty-year-old daughter, Helen. In shock, he was put up at The Murray Hill in the suite of rooms recently vacated by the British writer, Rudyard Kipling.

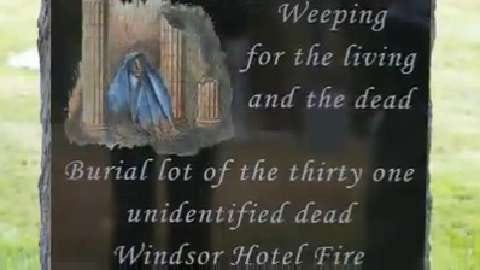

At final count, eighty-six persons perished, several lingering in hospitals before succumbing to their wounds. The April 3rd Evening Telegram reported that forty-five bodies were recovered, not all of them identifiable. Forty-one more remained missing. It was assumed the unclaimed would be buried in a potter’s field, but Mr. Leland pronounced the notion “sacrilege” and took it upon himself to see to their proper burial. The coffins of sixteen unidentified corpses and a seventeenth filled with sundry body parts were laid to rest at Kensico Cemetery in Westchester at the hotelier’s expense.

Inquest and Aftermath

Every day for the following week, the fire headlined newspapers, not only in New York but across the country and as far afield as England. As workmen sifted through the still-smoking ruins, revised rosters of the dead and injured were printed daily. An inquest was convened, and the following official story emerged.

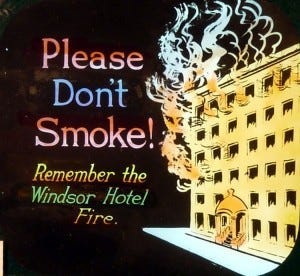

At 3 p.m., John Foy, a headwaiter at the hotel, was passing through the hall on the parlor floor on his way to the bank of bow windows to watch the parade. Ahead he spotted a gentleman guest light a cigar and then toss the match out the window. According to Foy, the strong breeze blew the lit stick back into the lace curtain. Within seconds, the curtain and surrounding draperies were aflame. Foy tried smothering the flames, but they swiftly spread beyond the windows to the corridor. Next, he rushed to the fire alarm box but when he pulled the chain, it broke. Finally, he raced down to the main floor to alert Mr. Leland and the front desk, crying “Fire!” as he went.

The careless smoker story had its skeptics. Charles Whiting Baker, managing editor of The Engineering News, cited the experiences of two highly creditable hotel guests, Mr. Stauffer, Vice President of The Engineering News and Colonel Cowardin, President of the Richmond Virginia Dispatch Company. Cowardin, a guest in a third-floor room, № 369, reported a charred odor as early as nine o’clock that morning, which worsened throughout the day. In his interview printed in The New York Times, Baker concluded the fire must have smoldered in the walls or flues from the third floor to the top on the southeastern side since morning.

Not all the news was a testimony to tragedy. Daring rescues were reported. A bicycle policeman, Charles Liebold, darted inside the burning hotel and single-handedly rescued five men from a lower floor, one of whom he had to haul over his shoulder and carry out.

There were civilian acts of courage as well. Alerted to the fire, Mrs. Duncan coolly marched her young pupils and two grown daughters, including Isadora, down the fourth floor stairs to safety. And the waiter, John Foy, who after alerting the front desk, continued down to the basement to warn the women working in the laundry.

Nor were all the rescuers two-footed. The Mail and Express printed a picture of Nell, the Dalmatian mascot of Hook and Ladder №21, who came through the fire but narrowly.

But by far the gallant heroes of the day were the firemen. New York Fire Chief Binns singled out ten of his top men for the Roll of Merit, but only one did he put forth for the Department’s highest honor, the James Gordon Bennett Medal for exceptional bravery in the service of saving lives.

Captain William Clark (my inspiration for Joe Kavanaugh in IRISH EYES) was awarded the Bennett in 1900. Clark carried off several daring rescues at the Windsor, including climbing to the second floor on a regular ladder, then using a hand-held scaling ladder to reach the third floor. From there, he managed to haul himself up to a fourth-floor window and carry out a trapped woman.

Legacy

The Windsor Hotel remains the deadliest hotel fire in New York’s history. Many (most) of the fire safety measures we take for granted today, such as fire stops and sprinkler systems, were absent from the 1870’s building. Even when the city’s building code requirements were updated in 1892, many commercial structures like the Windsor managed to skirt making structural updates.

A monument was planned for the unclaimed bodies buried at Kensico but the monies were not raised. Mr. Leland, who almost certainly would have championed the cause, had returned to Chicago where he perished of peritonitis on April 4, 1899. It wasn’t until 2014 that a stone marker was finally erected to remember the fire and its victims.

Thank you for reading History with Hope. Share this free post with other history lovers.

If you received this post and aren’t yet subscribed, you can fix that here!

Irish Eyes (Dec. 2023, Lume Books), Book 1 of Hope’s American Songbook series, spans 25 years of Gilded through Jazz Age New York, as seen through the eyes of spirited Irish immigrant, Rose O’Neill. Read more here.